One of the things you need to do when walking in today’s countryside is to let your imagination encompass the passage of time. Take a comparatively mundane example of a roadside marker you will definitely welcome—a pub. It is universally agreed that beer and other alcoholic brews such as mead have been around since at least the Neolithic (cereal cultivation may have originally been less about food than drink) so pubs in Megalithic Britain should come as no surprise. Beer has always been safer than water until modern times so a pub is a good start… use OS Explorer 297 or Landranger 104.

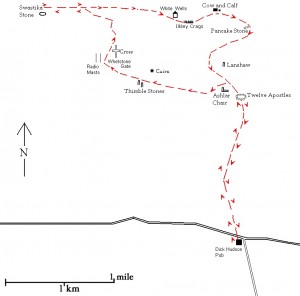

Route: Dick Hudson’s pub – Twelve Apostles stone circle – the Swastika Stone – the Pancake Stone – Dick Hudson’s pub.

Length: 12½ miles

From Bingley follow the Otley Road as far as the Dick Hudson pub on the right, where you will see a car park just behind (map reference SE 121422). Despite its modern name, the pub’s location offers several megalithic clues to the observant walker. In addition to providing the only car park for miles, it is high up at a point where one route crosses the moor north-south and the other (the Otley road) goes east-west. It is always worth noting the position of car parks on or near prehistoric tracks, they are often inconveniently on the summits of hills because they occupy a site that had already been levelled in antiquity. From its isolation Dick Hudson’s is clearly not a village pub but a watering-hole for long distance travellers. It was a tavern attached to an old farmhouse, which, due to a new road from Eldwick, lost its liquor licence, relocated to another farm and became, tellingly, ‘The Fleece Inn’ only being renamed Dick Hudson’s (after the landlord’s son) in the 1850’s.

Across the road from the pub is a gate giving access onto a footpath going uphill northwards (marked Eldwick Crag on the map). After about half a mile the path levels out and you come to a gate set in a drystone wall just beyond which is a milestone marked ‘To Ilkley 3 miles’. Perhaps it replaced a former boundary stone. During the course of the walk you will come across other milestones engraved with names and distances; these were erected in the seventeenth century when local justices were ordered to place waymarkers at intersections though it is worth bearing in mind that marked distances are also necessary when it comes to measuring angles. The path is boggy and narrow in places but the line of dark peat showing through the heather makes it easy to follow. As you head north you should be asking yourself what this isolated plateau is doing in the middle of the most built up area of Yorkshire. Presently its only commercial use is as a grouse moor, but formerly it may have been deliberately left uninhabited because of its suitability for astronomical surveying.

Another mile and another gate lead to another milestone at the half-way point between Otley and Ilkley where you will see on the horizon the Twelve Apostles stone circle close to where two trackways cross the moor. The stones are only three or four feet high though they may have been taller originally. In the middle of the circle which measures twelve paces across is a small pile of stones where once a standing stone was placed, thought to have been used for lunar or solar measurements[1]. The circle is more or less in the centre of the moor and some of the cup and ring stones appear to be aligned directly to it. In local folklore it was known as ‘the astronomical circle’.

Twelve Apostles stone circle on Ilkley Moor (map ref. SE12645)

The Twelve Apostles is beside the main north-south track that runs in an almost straight line between Dick Hudson’s pub and Ilkley. Just to the north-west of the circle by a fork in the track is a standing stone called Lanshaw Lad, a former menhir, on the boundary between Burley and Ilkley.

The stone circle was originally surrounded by a circular bank of earth and stones measuring fifty-two feet in diameter according to earlier descriptions but nothing remains of it now. No burials have turned up here and there is no reason to regard it as a ceremonial centre. As you contemplate the Twelve Apostles try not to muse on the supposed sacredness of stone circles; while it is true that they were, and probably still are, believed to exert a special aura, we just don’t know if our forebears viewed them as venerable objects. No doubt Megalithia benefited if religious sanctity got attached to what they regarded as strictly utilitarian objects so while in this isolated spot, ask yourself again, what was this plateau for? Looking at the surrounding hills the moor seems to be an anomaly, quite different from, say, the North Yorks Moors. Could it be the northern equivalent of Salisbury Plain, levelled ground suitable for long distance observations of the far horizon?

Just past the circle where the track forks, take the left-hand path marking another milestone or boundary stone, the Lanshaw Lad, which marks the highest point on the moor, reinforcing the idea of an observation platform. Keep following the track westwards towards the twin radio masts of Whetstone Gate past an isolated rock called Ashlar Chair which looks as if it once had cup-and-ring marks though they are now indistinct; the surface is decidedly pitted but makes a good seat. On the horizon to the west you can see another stone which is a trig point next to a cairn, unmissable in this treeless landscape. A straight line from the Twelve Apostles stone circle through the cairn will strike the Swastika Stone which is said to mark the point of the Major Lunar Standstill, the maximum moonrise on the north-west horizon, an event that occurs roughly every nineteen years. Whether this is the case or not, it is certainly true that similar claims are made for features found on the presumed southern equivalent of Rombald, Salisbury Plain, where the Aubrey Holes of Stonehenge are also said to be reconciling lunar and solar times based on the nineteen-year cycle.

Continue along the path past an imposing group of boulders marked on the map as Thimble Stones which look like they may have once been a stone circle, in any event they are a good landmark. Once past the Thimble Stones make for the drystone wall at the western boundary of the moor which the path follows northwards. This is a wet section though the path is paved with stone slabs in the boggiest places. The Sweet Track in Somerset, six thousand years old and the most ancient timber track yet discovered, was constructed to cross a mire and similar paths have been found in Yorkshire. Before modern road-building technology was available, a ‘corduroy track’ (laying logs) was the only feasible way to cross a boggy area. Archaeologists believe ancient man was fighting the effects of climate change; maybe ancient man, like modern man, simply took pains not to get his feet muddy. The more a route is used the muddier it gets, regardless of ‘climate change’, and the more used it is the more likely it is to be well maintained.

In under half a mile you come to Whetstone Gate on the left where you turn right along a stony track signposted to Ilkley. Why ‘Whetstone’? Was it a stone for sharpening knives? A few yards along the track you pass a stone cross known as Cowper’s Cross. It is described as a former “medieval trading cross” standing on a “Roman road” but these are characteristics of pre-Roman locations. With the modern signpost to Ilkley the cross is superfluous as a marker but its survival is interesting since most wayside crosses were destroyed or recycled during the Dissolution and/or the Reformation, though it should be remembered this is Pilgrimage of Grace territory. At any rate many of the larger crosses were broken up to repair roads, which were in a woeful state by Stuart times, the now-defunct monasteries having been largely responsible for their maintenance. This is a Cistercian hinterland and the Cistercians made a point of maintaining wayside markers particularly on trans-moorland routes that connected their houses.

The track starts to go downhill offering a welcome view of the much greener Wharfedale valley. On the right is a footpath which leads to the Badger Stone, another cup-and-ring stone, if you wish to make a short detour. Keep on the main track as far as the metalled road where you take the footpath branching off to the left which leads past a cottage, through a gate and then across an area of bracken until it meets up with a wide level track that runs east-west parallel with the valley. Just past the cottage you will see Panorama Reservoir on the right. A group of cup-and-ring stones, the Panorama Stones, used to be situated here before they were moved, three being placed less than a mile away opposite St Margaret’s Church in Ilkley in the late nineteenth century. St. Margaret, coincidentally or not, is a ‘dragon-slayer’ and a patron saint of childbirth.

A few yards further on is the Swastika Stone, protected on three sides by iron railings. The fourth side is right on the edge of a promontory on top of an almost vertical cliff-face, which makes access difficult. Have a look at the features on the horizon and ask yourself what is being measured. Megalithic Man was likely to favour high flat plains with an uninterrupted view of a level horizon for his more important measurements. The “swastika” cup and ring markings were copied in Victorian times at the height of an antiquarian mania though the markings on the earlier stone can still be just about deciphered. The swastika has a fifth unfinished semicircle on the lower right hand side like a handle which gives it a resemblance to a back to front Plough constellation and it is also strikingly similar to the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, the aleph. The stone itself is claimed to be in a direct alignment with the Twelve Apostles circle at the midwinter moonset. The swastika design occurs on stones in other parts of the world and has been compared to the Celtic cross. In Sanskrit svastika means ‘source of well-being’, not so different from Albion the old term for Britain meaning ‘all-good’. It is usually associated with sun worship, however the Swastika Stone faces north.

‘Swastika’ Stone, Ilkley

The relatively small area of Ilkley Moor has a conspicuous number of cup-and-ring petroglyphs, mostly on its northern perimeter overlooking the Wharfe valley. It is possible to ‘read’ cup and ring marks like a map, perhaps of the heavens above rather than the ground below; experiments have found the markings follow the pattern of constellations but in reverse, i.e. a mirror image, which suggests the ‘map’ was intended to be transcribed onto a piece of hide or cloth.

Return eastwards along the main track keeping to the left where it forks. The wall on your left is the boundary of Ilkley. Ilkley was a Roman fort and excavations have uncovered an altar with a figure holding two staffs or snakes dedicated to Verbeia. Though described as a Romano-British water goddess, Verbeia is unknown anywhere else and the Ilkley altar-stone dedicated to her is unique so the “Romano” bit is at least questionable. Roman settlements were not sited randomly but built on top of pre-existing shrines just as Christian church-builders in their turn covered pagan sites.

The path crosses a bridge over a beck and reaches a minor road; go straight ahead as indicated by a footpath sign partly hidden by bracken. The path is muddy and overgrown as you start climbing but soon widens out. At the T-junction turn right and follow the track uphill towards two white buildings marked as White Wells on the map. Just below the cottages is a bridge from where you can view the waterfall. Mineral water taken from the beck straight off the moor gave Ilkley its reputation as a spa town in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. If flags are flying it shows the café is open and there is a picnic table on the terrace with a view over Ilkley and the valley. The building is labelled ‘Baths’ and is supposed to have been used in Roman times although there is no evidence that the Romans used the springs. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century drinking or bathing here was thought to cure scrofula, which is interesting because the traditional cure, the Royal Touch, fell foul of Protestant reforms in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. No doubt Prince Charles will reintroduce these remedies when he ascends.

White Wells overlooking Ilkley

If White Wells was originally recreational or medicinal, it would be off the path. The fact that it is on the path indicates that it started life as a place of animal refreshment. There is even somewhere for people to throw coins ( i.e. a fee). Small coins because even in earlier times typical offerings (i.e. fees) were pins and fish-hooks rather than anything of great value. The fact is a spring is always a valuable asset and will be used for whatever the passing trade will bear at any particular era in history. You are now the passing trade.

On the face of things White Wells is a typical well-shrine next to a shallow pool for bathing, and a place for the superstitious to leave offerings in return for good luck. This is but a modern echo of what the Megalithics designed. Consider their problem: here was a natural spring gushing out of a hillside in an area where good water sources can be erratic. So a pool-and-well is constructed for the benefit of the animals and their drovers. Now, how to pay for it? The complex is cheap to maintain in the best Megalithic tradition but clearly, up here on the moors, there is unlikely to be enough traffic to justify a year-round full-time well-keeper. Solution: users throw small offerings into the well. This honesty principle always works where the charge is small, the service is appreciated and a sense of community is present. And, one supposes cynically, there is always the possibility of being caught. Notice, it is not generally worth anybody’s while to go into the well to retrieve the offerings nefariously because the well-keeper comes along regularly each week, when he knows it will be worth-while, but just to make sure, it is no bad idea to have plenty of folk-myths concerning good and bad luck, guardian-spirits, malevolent thingummyjigs and other aids to jog people into doing the right thing.

It would be interesting to see how far this very ordered state of affairs can be extended even into our own apparently more mercenary times. The attached café obeys Megalithic principles by being open only for three afternoon hours in the summer months but could in fact investigate whether walkers, the only contemporary passing trade, are “a community”. In other words, the café leaves out everything to be paid for voluntarily (in a locked repository). The principle is already well-established for drivers who can anonymously select and pay for produce from mini farmers-markets on country roads but obviously walkers are not yet of the moral stature of Toad. Future archaeologists will no doubt regard them as votive offerings. There are also the mysterious ‘money trees’ which are similarly associated with watery places but in areas lacking wells. Here coins were inserted into the bark of selected trees for later collection. It is always advisable when out and about to look for these folk reminders as a guide to what was really going on in the area. Very similar practices survive in rural areas as far apart as Siberia and India so it may be that the Megalithic System is a common heritage.

Carry on climbing above White Wells eastwards on the signed path which goes up and down and is strewn with boulders, past Ilkley Crags towards the Cow and Calf, crossing a beck where flat boulders serve as stepping stones. The Cow and Calf is an outcrop of boulders, popular with climbers and visitors, which is thought to have once been covered with cup and ring marks though none are visible now. Below is a car park and kiosk and a little way along the road is the Cow & Calf pub. On May Day a cow would pass between beacon fires on the ingle- or angle-stone. In parts of Scotland cups or grooves would be filled with milk on or around Beltane, said to be an act of rogation to ensure herds’ fertility. Some wells are specifically associated with offerings of milk, even cheese; a drover might not be able to pay in any other currency[2]. The absence of cup and groove markings on The Cow and Calf that are characteristic of many nearby rocks has been attributed to the numbers of visitors, the site being easily accessed from the road below via a footpath. A little further east is another prominent landmark on the skyline, the Pancake Stone, a logan or rocking stone.

The Cow and Calf, Ilkley

The Cow and Calf stones consist of a dramatic rocky crag and a boulder on the northern edge of Ilkley Moor. The larger rock used to be known as the Inglestone Cow. ‘Ingle’ is usually associated with fire, as in Inglenook fireplaces, from the Gaelic aingeal. But the true connection, given that the rock is spectacularly “angular”, is that the Irish word is likely to be via ‘angel’, in other words ‘angle’ is Megalithic and has been transferred to Irish. But St Rombald, who gives his name to the moor, was Irish so the etymologists might have got this one right on the law of averages.

The path continues eastwards parallel with the road. On the skyline to your right is a quite small but distinctive logan stone, the Pancake Stone. Make your way towards it using one of several narrow paths which are not well defined but as you climb up the going becomes easier. At the summit turn right above the logan stone which has cup and ring markings on top and go westwards for a few yards till you see a path on the left going in a southwest direction. This northern edge of the moor is famous for its cup-and-ring stones but they are hard to see in the heather. Why there are so many cup and ring marked stones clustered along the northern perimeter remains a mystery, they are not large enough to be useful landmarks from a distance so must have been intended for close-up viewing. Presumably they came to be used for more sophisticated purposes than that of merely putting people on the correct path. The path takes you to the main north-south track, easily seen as it is boarded for some of the way, where you turn left towards the milestone, visible on the skyline, still going in a south/south-west direction. The flatness of the terrain makes navigating straightforward and the Whetstone Gate radio masts to the west are distinctive landmarks.

Opposite the milestone is a footpath sign and the Twelve Apostles circle just beyond it. A short distance south of the circle is a small cairn where a path to the left leads to the Grubstones, marked ‘enclosure’ on the map, that may have been a stone circle, about a mile away. An annual perambulation, i.e. a boundary-marking walk, took place at the Grubstones, which were formerly known as Roms or Rums Law, on Rogation Monday, calendrically close to Beltane or May Day. The ceremony always ended with the chant “This is Rumbles Law”. The Grubstones site is on a former boundary line and members of the Masonic Grand Lodge of All England are rumoured to have met there.

To the east of the Grubstones is a cairn called The Great Skirtful of Stones, whose stones are supposed to have fallen from the apron of a giantess, Rombald’s wife, during a quarrel. The apron, oddly homely, is reminiscent of Hermes’ pouch or purse and the motif frequently occurs in megalithic lore (the protagonist can vary, other times it is Jack or the Devil strewing stones). It is also worth noting that one of the most distinctive elements of Freemasonry is of course the Masonic apron. Capstones, cairns, giant’s ‘tombs’ and other megalithic landmarks were as carefully sited as later churches and temples built by Masons in accordance with precise alignments. The main path leads straight on for a couple of miles back to Dick Hudson’s pub and the starting point of the walk.

[1] ‘Twelve Apostles’ is a manifestly Christian name, unusual for megaliths, but the circle once had thirteen stones so perhaps the removal of the thirteenth stone went with the Christianising of the name. The number thirteen occurs frequently in Welsh folklore, an allusion to the pre-literate calendar of thirteen four-week months that was superceded by the Julian system, in turn based on the Egyptians’ twelve thirty-day months.

[2] Milk was, and is, drunk by metal-workers as protection against ‘metal fume fever’, (also known as brass founders’ ague or brass shakes). A common motif in legend is dragons’ insatiable desire for milk, a curiously gentle request when set against their usual demands for sheep and maidens. Drovers could afford the Megalithian toll in milk but perhaps could not risk forfeiting the other two.

Leave a Reply