Ilkley Moor and the adjoining Bingley, Burley and Morton Moors are collectively known as Rombald’s, or Rumbles, Moor. The name is said to be that of a fabled giant, generally credited in folklore with superhuman feats in constructing these marvels, an explanation roughly as trustworthy as our own academic folklore that these things are geological in origin. At least our forebears understood that Great Minds were at work. But which great minds? There was a seventh-century infant prodigy, Rumbold, purportedly a Northumbrian royal, who lived for three days but managed to insist on being baptised with water from a hollow stone “too heavy to move”, in other words a megalith. His three-day life was sufficiently wondrous to merit a whole Anglo-Saxon Vita. But Rumboldiana is not limited to the north or to infants. The name of the first recorded priest at Avebury is St Rainbold; a well at Astrop, Northamptonshire near King’s Sutton (King’s Stone?) is dedicated to St. Rumbald as is another one with “curative waters” at nearby Brackley in Buckinghamshire. There is also a St. Rombold’s church, twelve miles away in Buckingham itself, where he is supposed to have died. His birthday is, naturally, the 1st November, i.e. Samhain.

St. Rombald or Rombaut also pops up across the North Sea, though here he is given a more realistic legend as an Irish-born missionary taking Christianity to pagan Europe in the sixth century. St. Rombald’s cathedral in Mechlin, Belgium, the town where this saint died, is noted for its flat-topped tower as well as a painting and a glass window of a Black Madonna[1]. Black Madonnas may relate to the Egyptian nature goddess Isis as another instance of the, mostly successful, incorporation of pre-Christian icons into Christianity.

Continental Megalithia has its own cast-of-characters, of whom Mary Magdalene seems to be head honcho, or rather Joint Honcho with St. John the Baptist, whose feast day, June 24th, is the same as Rombald’s[2]. This date, three days after the summer solstice, is the equivalent of Christmas, a few days after the winter solstice, and is probably an example of the way, especially in the more rigorously Catholic parts of Europe, that Christian and pagan dates were elided with a diplomatic lack of fanfare. The Rumbold nexus between Yorkshire and the Low Countries confirms the many historic ties between these two regions.

The Rhumbus

A connection can be made between Rombald, a lozenge-shaped plateau, and rhombus, an equal-sided parallelogram. Rhumb lines are mathematical projections which help in direction-finding when using a two-dimensional map to draw lines on the three-dimensional earth. In pre-literate times, before maps, a large flat plain and an unobstructed rhomboid plateau would have done nicely. In anatomy the rhomboid muscle is the one connecting the shoulder blade to the vertebrae of the spinal column. But who is getting inspiration from whom: the Palladium, a sacred statue of Ancient Greece that possessed great protective powers, was made from the shoulder-blade of Pelops and in Greek mythology Pelops was killed by his father, served up in a banquet at which his left shoulder was eaten, then resurrected and given a replacement shoulder-blade of ivory made by Hephaestus the smith. This association between smiths and non-metals is highly significant because smiths were a Neolithic, i.e. stone-working, creation of the Megalithics, before they turned their talents to metalwork. Rhombos is Greek for spinning-top, an allusion to the swirling ecstatic dance performed with the Palladium at its centre. This not only resonates with the May-pole Dance but might have further associations with the Whirling Dervishes who were originally the intellectual cutting edge of Islam and more specifically for our purposes originated in northern Anatolia, the well-known Megalithic hotspot and home of the Chaldeans. Various references to ‘Tops’ and ‘whirling’ feature in the Hermetic text of the Chaldean Oracles. In the Orphic Mysteries spinning tops represented the stars and planets.

Warp & Weft

Pre-Roman Ilkley is described as a stronghold of the Brigantes tribe, a town of some standing. ‘Brig’ is supposed to be a Celtic word meaning high and is also found in the Celtic areas of the Iberian peninsula north of the Douro but since it has the same root as burgh, brough and borough the true origins are evidently wider and earlier. The Brigantes were credited with creating an aristocratic or feudal society north of the rivers Humber, Don and Trent. Local tradition claims that the Brigantes harried Roman legions in Yorkshire though they do not appear to have disrupted proceedings for long and it is much more likely that the Brigantes co-operated with the Romans in the usual British ruling class fashion. And very sensible too.

Ilkley was a strategic trading post on the notoriously dangerous River Wharfe. The name Wharfe is of dubious origin, it is claimed to be a Celtic word meaning something like ‘the winding one’, but Wharfe is more likely to just mean wharf. Attempts to trace the etymology of Verbeia have linked ver– or wer– to weir and ‘turning’ words as in warp. ‘Warping’ boats in such a hostile river as the Wharfe would be a highly Megalithic occupation, and fish-weirs are also clearly Megalithian in that they derive maximum benefit from relatively little effort but require considerable group-capital to set up. In any case riverine fish-weirs tend to be in places also suited to fords, prime places for toll-collecting. It is noticeable that during the capital-poor Middle Ages it was the Cistercians and the Templars who were in a position to build fish-weirs.

Animal, Vegetable or Mineral?

Verbena, or vervain, a plant allegedly prized by the Druids, was gathered at daybreak and used for divination and healing and also worn as garlands. The Romans were said to dress altars with vervain but it may be that vervain is a generic term referring to green-leaved plants like myrtle, laurel, etc. used in rituals. Vervain could mean ‘twisting vine’, in which case Verbeia would be a prototype Green Woman, a female equivalent of the Green Man.

Stone carving of Verbeia

This ancient relief carving is in All Saints Parish Church, Ilkley. The outlines of the carving are so indistinct that it is hard to determine if she is holding a pair of snakes or flaming torches or staffs, all of which have obvious Hermetic associations. There may be a connection between Verbeia, the nearby Swastika Stone and Brigid, or Bridget, whose cross resembles a swastika (sun) symbol and is the patron saint of blacksmiths and midwives in Ireland.

In several European languages verbena is called “ironherb” (e.g. Eisenkraut in German and IJzerhard in Dutch which means ‘iron-hardener’); the association seems to arise from smiths’ use of vervain in metal hardening procedures, vervain being carbon, as in carbon steel. As indicated before, the entire area of ancient metallurgy’s use of vegetable alloys is a scandalously neglected subject.

We’ll Always Have Paris

In the south-east corner, close to the sea in what is now the East Riding, were the Parisii, thought to be related to the Parisii tribe who migrated to Yorkshire from the area around Paris. Since their names are the same this is a perfectly reasonable conclusion though it has been rejected by some prehistorians who claim that ‘the Brits just wanted to ape the more sophisticated manners of the Continentals’. The standard explanation for the presence of the Parisii is that they were fleeing from Caesar’s Gallic wars (though in fact they may have migrated a century or so earlier) but why did the refugees choose to go as far north as Yorkshire and why this particular area? A more radical view is that the French Parisians came from Yorkshire, hence the similarity of the names. One obvious underpinning for this argument is that the Trinovantes were a British tribe (Trinovantum = New Troy) and Paris was the hero of Old Troy.

From the piecemeal physical evidence, mainly burials, the Parisii seem to have kept their distance from the neighbouring Brigantes. But another way of looking at this kind of co-existence is to assume that the Parisii are a local élite, the Brigantes the rank-and-file. The well-known Percy family is worth considering in this context. The Percys themselves believe that their eponymous village, Perci in Normandy, is a reference to Persia which would link them back to Anatolian Iron Age roots. The association of horses including chariot burials with the upper classes and the common assumption that British horse culture originates from the South Asian steppes is all part of the same mélange. This might very well be entirely fanciful but the general point is that the upper classes have an astonishingly tenacious longevity in western Europe—Classical Roman families were still supplying popes into modern times—and Britain is rich in this kind of heritage, especially when it comes to the Neo-Megalithian Norman families.

The White Roses of Picardy

The term ‘Arras culture’ is used by archaeologists to refer to certain anomalous practices specific to this area of Yorkshire, for instance chariot burials (unique in Britain) in square-shaped barrows. Several hundred burials have been unearthed in the region and a Continental origin is assumed due to the similarity to burial sites in northern France and Belgium. But again it might just as well be the other way about. Most people nowadays associate Arras, the town in Picardy, with either the First World War battle-site or ‘behind the arras’ from Hamlet, Arras being a textile town famous for tapestries. So let us sort out what is really going on here. If we accept that Arras, Troyes and Paris form a triangle in northern France, and then add the British Troy Game, the Trinovantes, the Yorkshire Parisii and the Arras culture, they all seem to point to some connection not merely between prehistoric Britain and France but one that links both countries with the Eastern Mediterranean[3]. Neo-Megalithic links between the two regions continue well into historic times. The woollen industry of Picardy was a major outlet for the Cistercian-run Yorkshire wool trade and British precious metals employ the Troy weight, supposedly from the medieval market established at Troyes. Actually Troy weight is ‘London weight’ according to the English. In earlier times the kind of meticulous measuring process required for precious metals involved two particular ingredients: distilled water and mercury. This is all highly Megalithic of course but another, perhaps fortuitous, connection is the ‘poetic triad’: Mercury’s alchemical symbol is the swan; Shakespeare is the Swan of Avon; Troyes is the native town of Chrétien de Troyes, who essentially began the Grail romances; and Arras was a noted centre of troubadours[4].

The Longest Straight Track

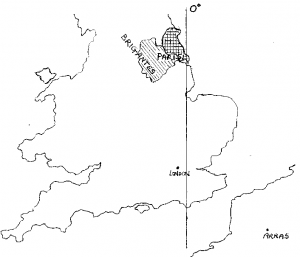

Yorkshire and Paris are also linked by the meridian line. The present prime meridian leaves the North Pole and never touches land until it reaches Holderness in east Yorkshire. Of course we are taught that the prime meridian is a very recent source of rivalry between London and Paris but in fact we can be reasonably confident meridians in general would be of some importance to long distance navigators such as the Megalithics.

Anciently, highways were always sanctuaries with a distant aura of royal protection surrounding the stones in general (later extended to churches), though by the Middle Ages the safety of travellers was guaranteed by statute rather than statue. Free-standing stone crosses, such as the one on Ilkley Moor, typical of town squares and crossroads, are unique to the British Isles and Ireland.[5] Ermine Street more or less traces the meridian line and leads straight to the English capital, London, on the Thames from the ‘Paris’ capital, Brough, on the Humber. Along the way it passes through Royston, said to be named after a cross variously written as Royse’s, Rohesia’s or Roisia’s, but the monument is more likely to have been a standing stone since Royston just means ‘King Stone’. The location of Royston is geomantically significant: on the two major roads of Ermine Street and the Icknield Way; the Michael Line; and on the meridian. Megalithically speaking, Royston is one of the most important places in Britain, there is even a hermit’s cave underneath the Ermine Street-Icknield Way crossroads. Investigate!

Map showing location of the Parisii and Brigantes

The Parisii settled in the south east corner of the East Riding in Yorkshire, the first area of land crossed by the meridian line, a fact which may have influenced their choice. If, as is claimed, they were fleeing from Caesar’s troops, they are likely to be Gaulish Druids since most Gauls were content to come to terms. Longitude was officially discovered by the French astronomer Picard using a triangulation method in the seventeenth century (A.D.) though Eratosthenes was using lines of longitude in the third century (B.C).

Petuaria, the capital of the (Yorkshire) Parisii, is at the head of Ermine Street and, coincidentally or not, lies almost exactly on the meridian. Officially Ermine Street started from London, Bishopsgate, and ended at York but in fact Ermine Street does not end at York but at Winteringham, on the south bank of the Humber opposite Petuaria, or Brough as it is now called. Ermine Street is of course the Street of Hermes (street means straight and straightness is the great Megalithic characteristic). A little east of Winteringham are ‘chalybeate springs’, chalybeate meaning ferruginous related to the Latin chalybs for tempered iron or steel. Chalybs refers to the Chalybes (aka the Chaldeans), a northern Anatolian people credited with the invention of commercial iron working. These Chaldeans are often put forward as the great mathematicians of antiquity, responsible for the 360 degrees of the world circle, making a neat connection back to the prime meridian and forging yet another link between the Yorkshire Parisii and Old Troy which was situated in northern Anatolia.

Helen

Another local feature to look out for is “Helen” names. Elen is the Druid Goddess of Roads and tends to turn up at interesting places. In classical mythology Helen is associated with Troy but the Christians claimed her by making the British Helen the mother of Constantine the Great and then the discoverer of the True Cross. Since Constantine, as it were, introduced Christianity, this makes Helen the mother-of-Jesus, in a manner of thinking. Constantine was the founder of Constantinople opposite Troy, so this relationship represents a further link between the two regions. The whole area on the north side of the Humber was part of a British kingdom called Elmet, officially founded by (Good King) Cole, father of Helen and grandfather of Constantine. There is also the Welsh Elen, Ellen of the Ways, who is equated with road-building in Welsh folklore. Sarn Helen is an ancient road that runs the length of west Wales starting at Caerafon opposite Anglesey. This Elen is reputed to have introduced monasticism into England, and monasteries as we shall see played a pivotal role in ensuring that Megalithia flourished into the Christian era.[6]

An obvious Helen site is Elloughton Hill just to the north of Brough, the terminus of Ermine Street, and therefore a suitable place to honour the patron goddess of roads. Ellen, like Artemis/Diana, is a moon-goddess so, unsurprisingly, the pub in Elloughton is ‘The Half Moon’. Speaking of pubs, down the road is The Green Dragon in Welton, whose church is dedicated to Helen and contains an effigy of a Knight Templar. St Helen’s church stands on a hill from where you can see an array of spires—York, Lincoln, Beverley and Howden—a characteristic Megalithic pattern. Welton’s main street is called Cowgate, presumably a payment point on a drover’s route. North-west of Elloughton is Arras Hill and the village of Goodmanham with its St. Helen’s holy-well and a prehistoric temple allegedly dedicated to Woden. Goodmanham is on a long distance path, now reconstituted as the Yorkshire Wolds Way, linking the North Sea coast to the Humber.

The World Pillar

Although there is a clear connection between Ermine Street and Hermes, the wider etymology of these names needs investigating. The most likely deeper meaning would seem to be Irminsûl, loosely translated as ‘world-pillar’ or ‘pillar of all people’, an Indo-European version of the world-tree. Early Irmin-pillars were made from tree-trunks, wooden not stone, with a shaped top sometimes described as the head of a deity but more likely a sun-disc. There is no mistaking their resemblance to hermai or Hermes-pillars.

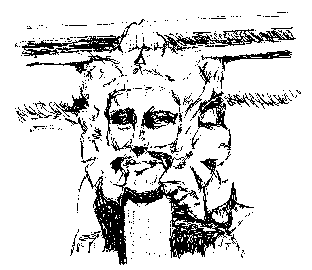

Herma or Hermes-pillar

Hermai are four-sided menhirs or stone pillars with the bust of Hermes at the top and often with a heap of small stones at the base. Offerings of food were placed by the stone markers, ostensibly for Hermes but in practice as payment (a hermaion in Greek means a lucky find, ‘a gift of Hermes’). The word men-hir, literally ‘stone-long’, is a term borrowed from Breton but in English, where the adjective comes before the noun, men-hir would be in reverse order; if it is written hir-men, its relationship to Hermes is much more obvious.

The tallest extant megalith in the whole of Britain, the Rudstone, is in the East Riding of Yorkshire at a highly significant meeting-point of roads and cursuses connecting Beacon Hill and Rudstone Beacon. Rudstone Beacon itself is on the meridian and is crossed by a strategic road aligned with the cursus. The Rudstone, at twenty-six feet, required an entire church to itself, All Saints’ church (All Saints = All Hallows = Hallowe’en = Samhain). The stone occupies the north side, the ‘devil’s side’, where people were not buried though, for some reason in this case, the stone is surrounded by graves. Certainly the locals seemed to have cherished their pagan monument, they provided it with a lead ‘hat’ in 1773. Rudstone’s name suggests ‘Rood Stone’, a rood being an ancient British measure (taught to schoolchildren in the phrase “rod, pole or perch”). The Rood Cross, the central feature of traditional British churches, almost certainly refers back to navigational cross-staffs which similarly combine the properties of a cross and a measure. Whether this connection was originally esoteric, the Christians decided it was and erected the ‘rood screen’, officially to separate the laity from the cross. One of the objects of the Protestant Reformers was to break down this separation but possibly an unstated reason was to get rid of yet one more Megalithic symbol. In any event the only rood cross surviving today is to be found, covered in greenery, in St. Mary’s Church, Charlton-on-Otmoor, Oxfordshire. Memories of its Megalithic origins seem to have survived the ages, the cross being dressed twice a year with a rope-like flower garland (i.e. the caduceus) on the saint’s day and on May 1st.

Hermes Through The Ages

Further south on Ermine Street, Thorney in Cambridgeshire is another point on the meridian. It has an abbey dedicated to Saint Fermin, who is also honoured at the St Farmin well in Bowes, North Yorkshire. Fermin is significant because his name appears to be a corruption of Ermine (i.e. Hermes) and according to tradition he was baptised by St. Sernin or Saturninus, said to be the first bishop of Toulouse, and known as St Cernin in Navarre (where he has a well too). Fermin and Cernin are the same person, at any rate they shared identical fates, both being martyred by a bull. The Megalithic link for all this is that St Fermin aka Cernin is a variation of the horned British god Cernunnos or Herne, Herne the Hunter frequently being conflated with Hermes. In fact, these western Hermes saints seem to represent Megalithic maritime trade routes.

It is always worth noting significant names in significant places. For instance Herm is one of the Channel Islands and is opposite Fermain Bay, on Guernsey. St. Sampson, after whom the traditional trading port of Guernsey is named, features widely in Brittany, Cornwall and west Wales but in England he occurs only once and that is in York, the central trading hub of the region. There has been a parish church of St. Denys in York since at least 1154[7]. It is Denis himself (Dionysus) who is most associated with bull cults via the underground caves where his initiates carried out their mysterious rites.[8] Dionysus is, as we have seen, a transitional figure between Old Megalithia and the newly-awakened Megalithic influences of the Gothic cathedrals.

Carving of St. Denis, Church of St. Dionysius (or St. Denys) in Kelmarsh, Northamptonshire[9]

The patron saint of France, St. Denis, is named after the Greek god, Dionysus. As with other gargoyles, the head of the martyr (he died by the normal method of sacral kings, decapitation) forms a waterspout. He looks like a Green Man, popularly associated with the pagan Dionysus on account of the vine leaves. The appearance of green men in churches and cathedrals in France and England coincides with the Gothic style introduced c.1137 by Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, when returning Crusaders, especially the Templars, came into contact with Middle Eastern Islamic styles of architecture or, alternatively, from Moorish Spain. Or, alternatively, it was wholly native.

However St. Denis is also conflated with the so-called Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, one of the pioneers of Neoplatonism and therefore one of the links between Classical philosophy and the European Renaissance. The Gothic cathedrals are by definition a Christian milieu but they flaunted their pagan underpinnings by putting Dionysian Green Man symbols all around for everyone to see.

Technically, Dionysus is god of the vine, a tree which is not native to Britain and certainly not to Yorkshire, so it is surprising to find Winestead in Holderness which, furthermore, has a church dedicated to St. Germain situated almost exactly on the meridian. St. Germain was a bishop of Paris and before that a renowned hunter, like Cernunnos, a stag-headed god particularly associated with the Parisii of Gaul. The name Germain/Germanus is a version of Cernunnos. Do not be put off by the slight arbitrariness of these connections for, as you google about the Ancient (and Modern) World, you will find yourself being drawn into a morass of interconnected clues, the only escape from which, after a life-long quest for the truth, is to be taken by Rhine maidens to Avalon. ONO.

Et in Arcadia…[10]

Hermes’ birthplace, Mount Cyllene in Arcadia, southern Greece, is the homeland of the Pelasgians, known to the Egyptians as the ‘Sea People’. The events surrounding these so-called Sea People are extremely obscure (orthodox historians even misstate their exploits by some six hundred years) but suffice it to say they played a pivotal part in the switch from Egyptian to Phoenician and to Greek dominance of the Mediterranean seaways. However, the Pelasgians turn up in our story because of St. Pelagius. This British monk of the fourth century AD is (in)famous in the annals of history because of his far-reaching conflict with St. Augustine, the African one not the British one, though they may not be two different people. The British saint’s Big Idea was there was no such thing as Original Sin whereas Augustine, speaking for the Church, said there had to be. All this is just code for Rome versus Carthage, orthodoxy versus heterodoxy, Classical Civilisation versus Megalithia. Anthony Burgess in The Wanting Seed deals with this battle and demonstrates with great finality that the world needs both Authoritative Discipline and Lords of Creative Misrule.[11]

Hands Across The Water

Bronze Age boats of sophisticated design have been discovered in the Humber. These ‘Ferriby boats’ are claimed to be the oldest boats found in Europe and were certainly sturdy enough to ferry people and cargo, including cattle, across this major obstacle. Ferriby simply means ‘ferry town’—don’t be put off by scholarly references to Danish place-names, ‘by’ is not particularly Danish, cf. the ancient mining town of Corby, whose emblem is the raven and was supposedly named by Danish settlers even though corby is Gaelic for crow. More to the point, since Denmark and the Humber are natural trading partners, it is impossible to tell who is borrowing from whom.

The number of ‘raven’ place-names on this coast has been attributed to Viking sailors, who being renowned navigators, took ravens on their voyages and relied on the birds to find the nearest land. But there is no special reason why Vikings should be given sole credit for this very widespread practice. Ravens are used everywhere in augury; in fact corvids generally are widely regarded as all-purpose omens, as in the popular rhyme still used when magpies, rooks or crows (it varies locally) are spotted: “One for sorrow, two for mirth; Three for a wedding and four for a birth; Five for silver, six for gold; Seven for a secret ne’er to be told”. Hermes’s day is Mercury’s day (mercredi, miércoles, etc.), our Wednesday or Wodin’s Day[12]. Woden/Odin was the Norse “raven-god” who was usually shown with a pair of talking ravens acting as messenger-advisers named ‘Thought’ and ‘Memory’. In Norse mythology birds or animals that accompany humans have a role similar to that of a ‘guardian angel ‘with the additional characteristics of being able to shape-shift and bring good luck. All very Hermes-like.

Ravenser Odd was once on the southernmost point of the spit of land called Spurn Head (‘Odd’ is cognate with Old Norse oddi meaning ‘tongue or spit of land’, note ‘cognate with’ and not derived from). For a century Ravenser Odd was a fishing village that provided ships with harbour facilities. The spit is said to be a leftover underwater glacial moraine, though it looks uncommonly like a harbour wall. Spurn Head, despite being periodically breached and washed away, has somehow resisted total erosion which makes one suspect, despite geographers’ claims that this is natural long-shore drift, that it is in fact the result of some kind of human intervention. But, as with Chesil Beach, these large-scale controversies can only be broached when the earth scientists begin to appreciate that they do not live in a world of their own.

Weasel Words

The word for ermine is virtually the same across Europe and applies equally to stoats and weasels, e.g. stoat in Spanish is armiño and in French hermine. This Continental conflation suggests we are once more in the confusing territory of ancient domestication and modern ferality.

Hermes’ familiar [13]

The stoat is a burrower and was thought to be the only animal that could kill a snake. This has resonances with Hermes’ brother, Apollo, the Python-slayer, and the Judaeo-Christian serpent,[14] symbolising cunning and (secret) knowledge. The stoat’s coat changes colour from reddish-brown to pure white when the temperature dips below a certain level and thus becomes the ermine, a word cognate with Hermes. The connection to Hermes recalls the swan whose plumage also changes, from the brown of cygnets to the white of the adult bird. Just as swans belong to the Crown and are protected, so ermine fur is reserved for royalty.

The problem here is that zoologists assign species on the basis of morphology when that morphology may not have arisen from natural selection. So, for example, warreners use ferrets to control rabbits but what are ferrets? Even today they can be both tame and wild. Is this possible with stoats, weasels, otters, polecats, pinemartens (and apologies if there is some double-counting there)? It is all very well breeding fierceness into large mammals like dogs who will either remain safely domesticated or can go feral with little further consequence, but breeding fierceness into small mammals guarantees their success when they escape into the wild. If warrens cover the land, and ferrets rule the warrens, what happens when warrening ceases? And don’t forget, ‘warrens’ are not just for rabbits; the further back in history, the more important this form of farming wild animals becomes. If we had not told zoologists that mink were introduced in historical times, would they have been able to tell us that there was something odd about mink in the scheme of British fauna? Once you understand that human affairs impinge on animal speciation, new vistas of possibility open. Imagine setting otters to catch trout, imagine beavers building and patrolling your salmon farm. The point is not whether these things happened or not, but what evidence of their happening would be left to us if they did. The evidence would be in the genes, morphology and behavioural characteristics of present-day animals (with a very little contribution from fossils) but then we shall be reliant on the Life Scientists to help us out. But beware, as with the Earth Scientists, these professional practitioners have their own nests to feather.

The male stoat-weasel is a dog, the female a bitch, and this ‘dog’ appellation suggests domestication; the critical juvenile form is called a kit, a ‘cat’ appellation, kit being short for kitten. The keeping of animals for fur does not itself require domestication though there is quite a lot of evidence that domestication increases breeding rate, so there is an economic justification for the step. But once captive breeding and/or domestication becomes established, large elements of the animal’s morphology pass into human control, whether by accident or by design. The stoat/ermine’s white coat can be assumed to be natural, but what of the black tip of the tail? Zoologists turn cartwheels in their attempt to explain it by natural selection but it is at least as uncomplicated to suggest that the characteristic was bred for—ermine tails feature on the flag of Brittany (formerly Armorica, ‘ermine-land’) as a badge of distinction. The black tip of ‘royal ermine’ is always cropping up on ‘armorial’ shields as chevrons.[15] Another unusual stoat trait is delayed implantation, most likely the result of human intervention since such an outstandingly useful means of ensuring the kits are born at the right time of year would be more widespread if it was a result of “adaptation to the seasonal environment” as is claimed.[16]

The Megalithics seemed to take a keen interest in white animals, so it is likely that in some species whiteness is engineered rather than natural. Whiteness symbolises purity in many societies and this may derive from the exploitation of the albino form that occurs naturally in so many domesticated species (unless of course albinism is itself a diagnostic of domestication)[17]. Perhaps the simplest explanation for, and original use of, white animals is the reindeer herders’ selection of white animals to lead the herd.[18] Reindeer are the archetypal wild-yet-domesticated species. There is every reason to believe that reindeer herding and the appearance of Cro-Magnon are coeval, in other words the entire brief history of man (as opposed to the interminable Age of the Hominids) is tied up with animal domestication. There is time enough to explode the fallacy of the hunter-gatherer.

[1] Mechlin = Michael. According to Wiki variations of Mechlin embrace Maglinia, Magliniensis, Meglinia, etc. Whether this points to a husband-and-wife team or whether they are genuine corruptions, the connection with Black Madonnas, John the Baptist, and other Continental contributions to Megalith-lore needs teasing out. Like Arras the town was famous for tapestries and seems to have been a magnet for Dutch humanists in the sixteenth century.

[2] The Baptist, the ‘Voice crying in the Wilderness’, was the leader of a water-cult. He has some of the trappings of John Barleycorn, a corn-deity, because his beheading took place at the time of the summer solstice, but is really better considered a latter-day ‘Megalithic hermit’. St John the Baptist churches are of strategic interest, for example the one at Findon near Arundel, Sussex is beside major prehistoric flint mines on an east-west route that passes between the church and Tolmare Farm, next to Tolmere Pond, in a particularly dry chalk area; about a mile away from its location on Church Hill are the earthworks of Cissbury Rings, which are themselves flint mines.

[3] Just to throw another iron into the fire, an immensely important prehistoric copper mine on Anglesey is called Parys Mountain.

[4] The river Aras marked the boundary of the Chaldean kingdom between the Black Sea and the Caspian. Their homeland was defined by the sacred Mount Ararat (the original source of tin) and the Aras river, after flowing past it across the Anatolian Steppe, turned east to plunge through the main tin-bearing lodes between what would later become Persia and Armenia. Its banks provided access to the main source of their wealth: Chaldea was ‘The Land of Tin’. The Chaldeans acquired a reputation as great mystics and many settled further west in Aramea, a name cognate with Aras.

[5] This astonishing revelation comes to us with the imprimatur of the Victoria and Albert Museum so it may not be true.

[6] St Martin of Tours is said to have done the same for France. Tour meaning ‘tower’ is similar to tor which suggests Tours was a Megalithic site. Geoffrey of Monmouth claims that Tours was established by Brutus, the eponymous founder of Britain. The cathedral schools of Tours and Chartres were leading lights of Europe’s twelfth century ‘Renaissance”. In the thirteenth century Tours cathedral was rebuilt and dedicated to Saint Gatien who is commemorated by Sangatte in Normandy, so handy for cross-Channel traffic that it is the site of the Channel Tunnel terminal and illegal immigrants trying to get to Britain congregate there. Its English twin is Sandgate on the Kent coast. British -gate towns like Ramsgate and Margate are highly Megalithic.

[7] In Cornwall St Dennis, formerly St Denys, is overlooked by a church on top of a conical hill (Tredhinas in Cornish). The name, historians assure us, is from dinas meaning ‘dun’, the site being described as an Iron Age hillfort; in view of this linguistic connection one might expect them to wonder why the countryside is not littered with Denis names.

[8] The thirteen-month calendar was anciently divided into three sections which the God of the year represented in turn as a bull, a lion and a snake, the first five months as the bull. Orphic mystics, followers of Dionysus and from whom the Pythagoreans derived most of their doctrines, were obsessed with numbers which they revered as the essence of the universe, of order and of language (Logos), and their alphabet was linked to the yearly cycle. The alphabet was extended to twenty-two letters including seven vowels, presumably to reflect the 22:7 ratio of pi, a long-time secret formula for the relation of the circumference of a circle to the diameter.

[9] There are three churches dedicated to Dionysus /Denys in Northamptonshire, one of which is in Cold Ashby, the highest village in the county. ‘Cold’ and ‘Kel’ names may be a Chaldean rather than a ‘cell’ reference. Look out for Chalfonts and Chalburys with nearby chalybeate springs.

[10] Poussin of course knew all this.

[11] The Pelasgian alphabet, like the Irish one, reputedly had thirteen consonants and in Greek mythology Hermes invented letters from ‘the flight of cranes’. Thoth, the Egyptian inventor of the alphabet, was an ibis-headed god, an ibis being a sort of crane.

[12] The seven days of the week had corresponding sacred trees in Ogham, Wednesday’s tree being hazel, the tree of wisdom and eloquence, and associated with Hermes. According to Celtic folklore hazel nuts dropping into sacred wells were eaten by fish and produced the Salmon of Wisdom (and Solomon). It is likely that hazel nuts, easy to both carry and conserve, were used as toll-currency to pay the hermit or ‘wise-man’ (hence the phrase “nuts in May” when otherwise there would be no nuts). Traditionally British dowsers use hazel rods with a Y-shaped fork for their divining which chimes with Megalithic hermits knowing just where to find water, but being very mysterious about their sources.

[13] Hecate, the female equivalent (some say mother) of Hermes, had two familiars, a black dog and a polecat (or a weasel, or ferret…. or stoat …). In medieval lore the ermine, i.e. stoat, symbolised purity, harking back to its partnering with Hecate, moon-goddesses being invariably chaste as well as huntresses. Ferrets are still trained to help farmers hunt rabbits, the most likely reason for their domestication in the first place. Not domesticating can prove disastrous— when stoats were introduced into Australia and New Zealand to keep the rabbit population down, they hunted everything except the rabbits.

[14] Serpent is etymologically linked to Seraphim, a composite Hebrew word, raph meaning ‘healer’ and ser meaning ‘guardian angel’. The serpent was the symbol of the healing arts, hence the snake-entwined caduceus of Aesculapius (the Greek god of medicine).

[15] According to Burke’s General Armory, the earliest coat of arms yet discovered, belonging to a count of Wasserburg (d. 1010), is in the church of St. Emeran at Ratisbon. Hermes, aka Emeran, is the archetypal herald. But lower down the social scale, in Cockney rhyming slang, weasel means coat (“weasel and stoat”).

[16] Another animal that has delayed implantation is the seal, an important food resource for humans in the Arctic. Interestingly, male seals are called bulls, females are cows. The pups have white coats when they are born, later turning dark grey. It may not be entirely fortuitous that the faces of baby seals (before being clubbed to death) excite the outrage of actresses. There is some reason to think that domesticated species are chosen /selected for their human appeal. Next time, have a look at the barn owl and decide a) why it is so appealing and b) why it is white, then c) you will understand why they still live in barns even after having gone feral.

[17] Albinism occurs in human beings, which raises the question of whether human beings are a domesticated species. Since domesticates are invariably smaller, gracile versions of a contemporary wild species, and human beings are a smaller, gracile version of Neanderthal man, our being a domesticated species is not in itself unreasonable. But this in turn raises the question of who domesticated us. The obvious candidates are shape-shifting lizards in the royal family who arrived here by space ship from the Pleiades but the evidence is patchy.

[18] Reindeer is a Scandinavian word, hrein meaning pure or white, which is downright bizarre since they aren’t. In certain herding societies a white reindeer is chosen as lead animal and regarded as the herder’s spiritual protector, similar to but more potent than a ‘guardian angel’, that would die in its owner’s stead if required.

Leave a Reply